Five Architecture Choices to Make Before Your Data and Analytics Renewal Begins

09.01.2026 | 9 min ReadCategory: Data Platform | Tags: #Data Platform, #Architecture, #Data Engineering, #Data Modelling

Lessons from complex data platform and analytics programs

Introduction

In large data and analytics programs, two things are usually fixed: the ambitions and the milestones. Much else can be discussed – until suddenly it cannot. That is typically when architecture discussions become expensive.

It is tempting to start building early, thinking you can land the difficult choices along the way. Agile development can absolutely work well, but only if you are clear about what can actually be iterated on safely – and what becomes a bottleneck if it remains unclear.

Some choices are like that: they affect the entire production line for data. If they are not made early, you get “agile” as a method, but “ad hoc” and technical debt as the result.

This article describes five architecture choices that we believe should be made before building starts. Not because it is nice to have “architecture in place,” but because it reduces the risk of rework, delays and loss of trust when the platform is to be adopted – and increases the chances that you choose something the organization can actually manage over time.

The choices are based on our own experience and cover the following areas:

- Data platform choice: architecture is more about risk than features

- Data modeling principle: structure that must withstand both pace and ownership

- Layering and standards: the prerequisite for collaboration at scale

- Quality: something that must be built into the process

- Trade-offs: time and quality are often constraints – scope and complexity are the control variable

1 Data platform choice: architecture is more about risk than features

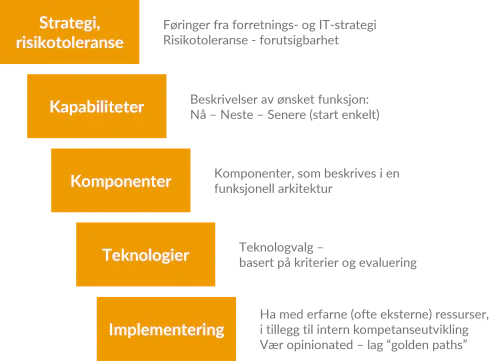

Platform choices often end up in a feature discussion: “does it support X?”, “does it have Y?”, “is it integrated with Z?” In practice, we see that large programs rarely fail on functionality. They fail on predictability. When multiple countries, domains and teams deliver in parallel, the platform choice becomes primarily a question of: How much uncertainty can we tolerate within the timeline? What is good enough for now?

Platform choices should in practice start by agreeing on which capabilities we need early – not which tool we like best. What must be in place from the start is primarily what enables the team to build data flows efficiently without building debt, and what enables you to operate data flows in production so that users actually trust them. Capabilities that primarily support other types of use cases can often wait.

A useful way to structure the choice is to link capabilities to platform components (storage/compute, ingest, orchestration, transformation, catalog, security, monitoring/observability) and evaluate technology choices per component.

Some choices become long-term, while others can be swapped more easily along the way – if you have clear standards and interfaces. When choices are difficult, we recommend a simple evaluation matrix with weighting and scoring, so that you optimize for the whole and delivery certainty – not for individual components.

Even with the right technology, you can make the implementation unnecessarily difficult. Typical stumbling blocks are:

- too many ways to do the same thing

- too few “golden paths”

- manual deployment and lack of quality gates

- unclear responsibility in operations

Bring experienced people in early. It is surprisingly easy to go astray and create extra work for data engineering and the data platform team for the remainder of the program. Sort out what you can start simply with (basic error alerting, basic monitoring, a simple data catalog that can be expanded) versus what must be a solid foundation from day 1 (access control, data contracts, standard deployment patterns and clear interfaces).

2 Data modeling principle: structure that must withstand both pace and ownership

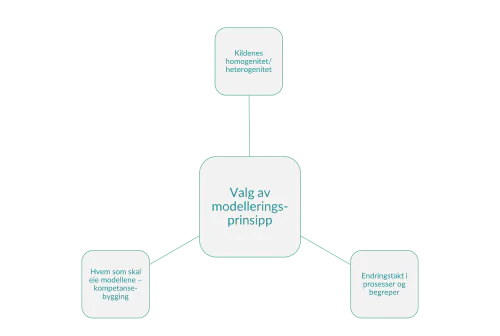

Data modeling quickly becomes a question of preferences and what architects and data engineers are familiar with. That is rarely productive. What is productive is talking about context and consequences.

The choice of modeling principle affects:

- how quickly you can deliver the first “good enough” version

- how much governance and competence is required to stay on course

- and how easy it is to transfer responsibility to the line organization

Some patterns (such as Data Vault) are strong when sources are many and poorly harmonized, and when change is the norm. Others (such as 3NF-oriented standardization and harmonization) often provide a faster path to functioning analytics when sources are fewer and more similar in data structure.

Here are three things that should determine the choice:

- How heterogeneous is the source landscape (now and in the foreseeable future)?

- How much change do we expect in processes and concepts during the program?

- Who will have long-term ownership of the model – and how do you build competence early enough to actually manage and further develop it?

Document and lock the decision: Lock the principle early and document it in a decision log. It is cheap to choose one path, expensive to support two – or change your mind along the way.

3 Layering and standards: the prerequisite for collaboration at scale

Layering, naming and standards often end up in the “we’ll deal with it later” category. That is a classic. And it rarely comes alone – it comes with:

- duplication of logic

- unclear expectations

- and discussions about where errors actually originate

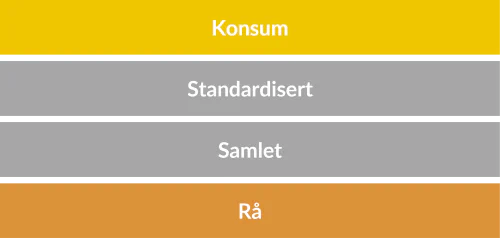

Clear layering provides a shared language for both developers and users. The most important thing is not the name of the layers, but that developers and users can have a clear expectation of what the layer should deliver. It makes it possible to deliver in parallel without everyone having to understand everything. It also makes troubleshooting far more precise: where in the value chain did the deviation occur?

Here is an example of a simple, explainable layering:

- Raw: This is what we received from the source, full history and traceable.

- Standardized: Cleansed, normalized, technically harmonized.

- Integrated: Integrated across sources, with shared concepts and dimensions.

- Consumption: What can be used in reports/KPIs – with quality and governance. Adapted to the use cases.

“Standards” does not mean documents. Standards means that two teams solve the same problem the same way – without having to meet three times first. Standards can often be operationalized through naming conventions, templates, init commands, CI/CD requirements and code examples. But standards do not work by themselves. In practice, they must also be enforced. That means someone has the mandate to decide “this is how we do it here,” and that deviations are caught in the delivery flow (for example through pipeline gates and code review). With 2-3 teams without decision-making authority, things quickly become chaotic, no matter how nice the standard is.

4 Quality: something that must be built into the process

Quality is rarely a goal in itself. Quality is a prerequisite for anyone to dare to use the data, and for the program to earn renewed trust. The problem is that quality is often defined as “we just need to be careful.” That is not enough. Architecture and ways of working must make it concrete.

Good quality assurance in an analytics program typically comes down to three things:

- Correctness: The numbers must be reconcilable against current reporting where continuity is expected. We must also have a plan for how to handle historical data, and how important it is that it can be used on the same structure as new solutions.

- Stability: Data flows must be stable and capable of running with a predictable update interval.

- Operability: It must be possible to understand, monitor and fix the platform without being dependent on specific individuals or the vendor in daily operations.

Quality means that what is delivered works, can withstand operations, and can be owned going forward. But in the data world, “quality” is not just an IT discipline: the quality that users experience in numbers, KPIs and reports must be owned and governed by the business owner. Platform and data teams can (and should) build the mechanisms that make quality possible to measure, test and monitor – but the content, definitions and acceptance of “good enough” must be anchored with those who own the process and the result.

Create a simple reconciliation baseline per domain and delivery package: which numbers are reconciled, how, and who signs off. It is surprisingly effective. This must be worked on in the definition of each delivery, together with the owner and users of the delivery.

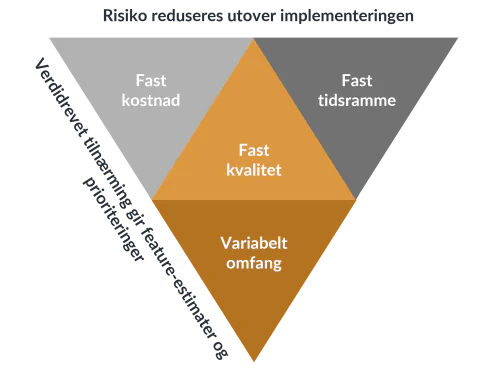

5 Trade-offs: time, cost and scope can be discussed – quality is a given

The most underrated architecture choice is not about technology. It is about which compromises you are actually willing to make.

My experience is that this works best when the program is explicit about the following:

- Time is often a fixed constraint. At the same time, some milestones are “sacred” without real consequences. Therefore, find the actual consequences of shifting the timeline before you lock everything down.

- Cost is often a constraint. It may be a significant investment approved by the executive team, and one you want to maintain.

- Quality is the baseline for what is delivered. Data deliveries must be correct to be usable, and the platform must be operational and manageable.

When time and cost are constraints, and quality is a given, it is usually scope and complexity that is the real control variable.

Scope is therefore the variable you should manage by. Minimum viable scope (MVP) is the management tool. It makes a big difference in the steering committee: When something goes wrong, you can adjust scope and complexity without having to negotiate about data correctness. That is a significant difference.

Create a prioritization list: If you start “discussing quality” in the steering committee, it is often a sign that the scope is not clear enough. Create the prioritization list at the outset, and discuss completion criteria (minimum and desired) for each individual delivery.

What do you do with this in practice?

This is not an invitation to write an architecture bible before you start. Quite the opposite.

A pragmatic approach we often see working:

- A short decision period (typically 2-3 weeks) with concrete workshops

- One page per decision: criteria, choice, consequence, and “what does this mean for the teams in practice” – including what competence must be in place and how you build it while you deliver

- A clear decision owner (often CIO/CTO or equivalent)

- A decision log and a simple change process when needed: Decisions can be changed, but then it must be worth the price. Facilitate for lead developers to propose improvements – and put technical debt on the table before it becomes permanent.

This makes it possible to start building early – without starting in the wrong direction.

Conclusion

Architecture in data programs is rarely about finding the perfect solution. It is about making a few deliberate choices early, so that the rest of the delivery can be agile in practice – not just in words.

If you land these five choices early, you often get:

- higher velocity,

- less friction between teams,

- fewer surprises in production,

- and easier ownership and further development over time – because you choose solutions the organization can actually manage, and build competence while you deliver, not afterward.

Bring the discussion to the steering committee and allocate the time required to land the basics. It does not slow down the program. It saves you time spent on rework and the consequences of unclear choices – and increases the likelihood of lasting, good solutions.