Rulebook and portfolio

08.02.2026 | 8 min ReadTags: #data products, #data mesh, #data governance

Keep the word 'data product' useful: product vs component, lifecycle, domains and ownership.

Rulebook: What we mean when we say “data product”

The term loses value when everything is called a product. You end up with a catalogue that looks impressive but does not help anyone make safe decisions.

The classic spiral looks like this:

- the catalogue grows large, but little is safe to build on

- people create copies “just in case”

- change becomes disruptive, because nobody knows who actually owns what

The rulebook below is designed to keep the word data product practically useful: few products with high signal value, many components without false promises.

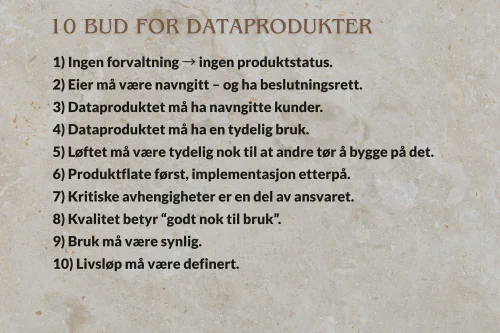

Ten rules that separate product from component

1 No governance –> no product status. If you do not have the capacity to uphold a promise over time, “product” is just an expensive label.

2 The owner must be named — and have decision-making authority. “Owner” means: who can decide on definitions, prioritisation and change — and who responds when something breaks?

3 The data product must have named customers. If the target audience is “everyone”, it is often a sign that you do not know who actually uses it.

4 The data product must have a clear use case. Not “for analytics”, but “to make X possible for Y”.

5 The promise must be clear enough that others dare to build on it. Access, refresh, quality signals and change practices are often sufficient.

6 Product surface first, implementation second. What you promise is the interface towards usage. The engine room should be refactorable without everything becoming an incident.

7 Critical dependencies are part of the responsibility. If the promise depends on pipelines, reference tables or quality jobs, the product team must own the consequences — even if the implementation may reside in several places.

8 Quality means “good enough for use”. A few tests that target the actual usage beat many generic tests you never act on.

9 Usage must be visible. If you do not know what is being used, you cannot prioritise, govern or deprecate in an orderly way either.

10 Lifecycle must be defined. “Pilot”, “active”, “deprecating” and “retired” is a simple way to prevent everything from lingering forever.

Here is a small illustration you can print out and frame. And perhaps hang in the hallway at home — or at the office…

“Team” and “owner” does not mean a Slack channel

Product status only makes sense when you can point to four things — briefly, concretely and without hero stories:

- Mandate: who makes decisions about definitions and change?

- Capacity: who actually has time for incidents and requests?

- Contact point: where do customers get answers without being dependent on a specific person?

- Run cost: who owns the prioritisation of operations/compute/support? (It is sufficient to own the prioritisation. You do not need to charge back every query.)

If you do not have this, it is better to call the deliverable a component for now.

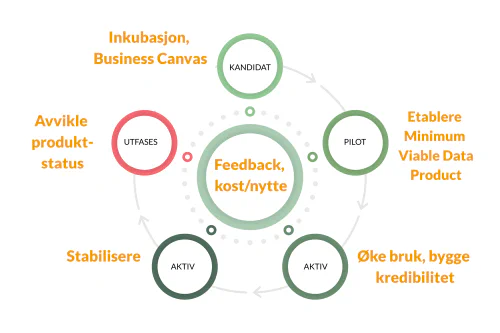

Lifecycle: make status visible in the catalogue

A simple status on the product page is often enough to make the catalogue more truthful:

- Draft – idea/work in progress, no promises

- Pilot – a few customers, limited promise

- Active – the product promise applies

- Deprecating – replacement is defined, deadline and migration are described

- Retired / downgraded – no longer a product (component or removed)

The point is not to be “process-mature”. The point is to make expectations explicit before someone builds two quarters’ worth of logic on something you were actually planning to discard.

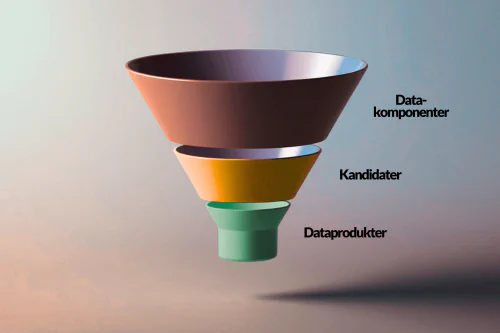

Three tiers that make the portfolio more pragmatic

In practice, you need a language for three types of deliverables:

- Data product: managed product surface with customers, a promise and a lifecycle

- Component: building block (table, model, pipeline) without a product promise

- Experiment: temporary deliverable for learning, can be upgraded later

The litmus test is simple: If you remove the deliverable tomorrow — do you know who would miss it, and do they know who to call?

Product portfolio in practice: what is a product, what is “inside”, and what does it cost you?

Once you have a language (product/component/experiment), you can also manage the portfolio. Here are two practical steps that often deliver the most impact per calorie:

- Give product status to the few things that are actually important and shared.

- Give component status to the rest — but make ownership and purpose visible.

Data product or component? A simple decision table

| Situation | Data product when… | Component when… |

|---|---|---|

| Reuse | multiple teams build on it | one team uses it locally |

| Risk of failure | failure is costly (money/compliance/governance) | failure is mostly annoying |

| Change | change must be handled in a controlled manner | change tolerates more ad hoc |

| Customers/value | you can point to customers and purpose | “maybe someone needs this” |

| Governance capacity | you can uphold a promise | you do not have the capacity (and that is ok) |

Data that is not a product: components, domain responsibility and lightweight governance

Not everything should be managed as a data product. But everything that is used (and everything that can be misunderstood) needs a minimum of order — otherwise “self-service” becomes a social experiment.

Components are building blocks: tables, models, intermediate layers, pipelines. They can be critical, but they do not have a promise you market as a “stable product surface”.

Minimum practices for components:

- which domain it belongs to

- who owns it (team) and contact point

- one sentence about purpose

- classification (especially for sensitivity/PII)

- simple lifecycle status (active / under change / being phased out)

- lineage/dependencies (roughly)

When there are named customers who would complain if this changed without notice, you are in data product territory.

Ownership and domains: who decides, and who governs?

This is where many “data product” initiatives fall short: people agree on a definition, but not on who will stand behind it when everyday reality kicks in.

What do we mean by “domain” here?

A domain is an area where someone has the mandate to define concepts and rules, because they own the process and the consequences.

This does not mean the domain map must be perfect before you start. It means you need an address for disagreement.

Data ownership: the part you cannot avoid

Two things that are often conflated:

Business ownership of semantics and rules Who decides the definition when there is disagreement?

Product/operational ownership of the product surface Who manages the promise to the customers: access, quality signals, change and support?

This can be the same team or split, but the responsibility must be clear. Otherwise you get a lot of “we thought you owned it”.

Platform team vs product team

- The platform team delivers standards and “golden paths” (build, test, deploy, catalogue, access, observability).

- The product team owns semantics, product surface, prioritisation and change.

- The domain owner/business shows up when definitions need to be settled.

Scale: how many data products can you sustain?

As many as you can actually manage with quality — with customers, a promise and a team that responds.

The number of data products should not be driven by the number of tables, but by the number of product surfaces you have the capacity to keep stable over time.

- Too few –> monolith: one large deliverable nobody dares to change

- Too many –> low signal value: hard to find “the recommended one”

Three categories for governance

- Data product: managed product surface with a promise

- Component: useful building block without a product promise

- Candidate: could become a data product with increased usage or higher risk

Usage must be visible

Choose 1-2 usage signals and start simply:

- consumption in BI/semantic layer

- query/access logs on product surfaces

- number of named consumer environments in the catalogue/README

- upstream/downstream in pipelines

Lifecycle: make expectations visible

Product vs component is about what something is. Lifecycle is about how safe it is to build on right now — and what happens when it changes. Without a visible lifecycle, the catalogue quickly becomes a list of “things that exist”, and sharing becomes person-dependent: people ask in private messages whether this is supported, whether the definitions are stable, or whether it is on its way out.

A simple lifecycle makes it possible to be honest without being heavy:

- Candidate means “no promises”

- Pilot means “a few customers and short feedback loops”

- Active means “the product promise applies”

- Deprecating means “we have a replacement, a deadline and a transition”.

The point is not as many statuses as possible — the point is fewer surprises, clearer prioritisation and tidier clean-up.

Typology: four common data product types

A typology makes it easier to choose the right level of expectations (and to prevent everything from ending up in the same “generic dataset” box).

| Type | What it is | Typical customers | Typical product surface | Typical promise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Master and reference data | Identity and references that must be consistent (customer, product, org, calendar) | Many domains | Table/view + history, optionally API | Stable identity + controlled change |

| B Domain foundation (events/facts) | Orders, payments, measurements, returns – with time logic | Multiple teams | Table/view, event feed, API | Semantics + keys + time logic |

| C Use-case-oriented data products | Built for a process/end result (impact, planning, risk) | Product/process teams | Dataset, metrics, feature store | Fit-for-use for one consumption surface |

| D External data products | Shared with partners/customers | External | API, export, event feed | Contract, support, strict change management |