Value

08.02.2026 | 5 min ReadTags: #data products, #measurable data value

Why data products are actually worth the effort – and how you measure the impact.

Why should you care about data products?

Because the alternative becomes costly in terms of time, friction and risk.

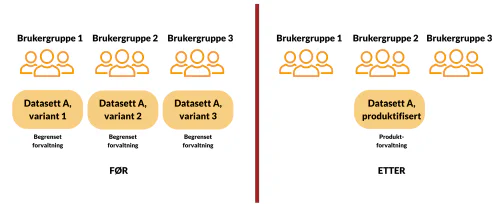

The classic pattern is familiar: Team A delivers “some data”, Team B copies and adapts it (to be safe), Team C builds on the copy. The result is fragmentation: multiple variants of “the same truth”, more run cost, more reconciliations and lower trust.

It is tempting to think this is “just” a bit of extra SQL. In practice it quickly becomes a systemic problem:

- Different definitions live side by side, with nobody knowing which one is “official”.

- Change becomes dangerous, because nobody has an overview of who uses what.

- Errors become silent, because discrepancies are discovered after the fact (often in a meeting, not in a pipeline).

- Reuse does not happen, because the safest strategy becomes creating your own copy.

Data products are not a magic solution. But they give you a tool to make a few deliverables stable enough that others dare to build on them — and to make cost/benefit visible enough that you can prioritise.

Signs that you need a “product” and not more tables

If you recognise several of these, you are probably in data product territory (or heading there):

- “Where does the number come from?” takes longer than making the decision.

- Two dashboards show different answers to the same question.

- People say “we don’t dare use that table” (and create a copy).

- Small changes upstream create large ripple effects downstream.

- You have things you never dare to delete, because the consequences are unknown.

When costs are measurable, value should be too

Every data product has concrete costs: compute, storage, operations, governance, support and further development. Then it is reasonable to be concrete about value as well — without overcomplicating things.

A practical approach is to talk about cost to serve in a simple way. Not to “chargeback” everything, but to prevent products from living forever on autopilot:

- Technical operations: execution, storage, observability, incident handling.

- Coordination cost: reconciliation of concepts, clarifications, meetings, “can you explain this join?”.

- Change cost: breaking changes, migrations, parallel interfaces, clean-up.

- Risk cost: wrong decisions, compliance breaches, loss of trust (which causes people to stop reusing).

When you do not make value explicit, you often get one of two unfortunate effects:

- Everything gets to live (because “maybe someone needs it”), or

- Everything gets measured and becomes noise (queries, number of tables, “popularity”) — and you end up optimising for the wrong things.

The goal is not a perfect business case. The goal is a good enough decision basis for prioritisation and portfolio management.

Concrete value hypotheses and metrics (examples)

Below are examples of value hypotheses that are easy to explain, and metrics that can be used without building a data warehouse to measure the data warehouse.

| Data product | Value hypothesis | Metrics (1-3) |

|---|---|---|

| Forecast/features for planning | Better planning by having multiple teams build on the same features/model output over time | Planning variance - share of decisions using the product - time spent on clarifications |

| Orders/order lines (event logic) | Less reconciliation through one status model and one time logic | discrepancy cases - time to period close - number of duplicate variants |

| Metrics layer (KPI) | Consistent KPIs across reports and teams | KPI conflicts - adoption in reports - time from change to updated consumption |

| Customer 360 – Core | More consistent customer view and less misuse | time to customer lookup - discrepancy in customer figures - number of consumer environments |

| Consent foundation | Lower compliance risk and fewer campaign errors | discrepancies/complaints - time from consent to effect - share of campaigns using the foundation |

| Product catalogue for analytics | Better assortment and pricing decisions | coverage on key attributes - number of local mappings - time spent on data cleansing |

To make this more manageable, it is useful to distinguish between three types of signals:

- Adoption (usage): who uses the product, and in which surfaces? (consumer environments, dashboards, jobs, API clients)

- Impact (benefit): what improves when the product is used? (time saved, fewer discrepancies, higher accuracy)

- Operating cost (run cost): what does it cost to uphold the promise? (incident rate, compute, support time)

You do not need all three from day 1. But if you never look at run cost, the portfolio quickly becomes a collection of “perpetual projects”.

How to measure without overdoing it

A simple practice that often works:

- Choose one value hypothesis per product (in plain language, not consultant-speak).

- Choose 1-3 metrics that you can actually monitor monthly.

- Tie the measurement to a decision: “If X happens, we do Y.” (Example: if adoption is low over 90 days, consider downgrading to component or adjust the product surface.)

Rule of thumb: metrics that change slowly are fine — as long as they change in the right direction when you take action.

Common traps

- “Number of queries” as value: high query rate may mean value, or just poor modelling and a missing semantic layer.

- “Number of tables” as progress: more engine room is not the same as more reuse.

- “Everyone must have SLOs” from day 1: SLOs without response practices become decoration.

- “This is for everyone”: unclear customers give unclear priorities, which give unclear product surfaces, which give copies.

If you are only going to do one thing: make the value hypothesis clear enough that you can say no to things that do not help the customer — and yes to what makes the product more reusable over time.