Interfaces first: sharing and data contracts

08.02.2026 | 4 min ReadTags: #data products, #data contract

The data product is the interface – the engine room should be refactorable without consumers noticing.

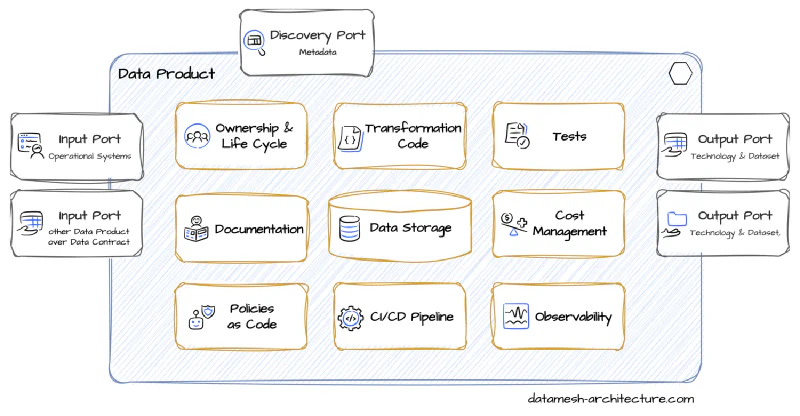

The data product is the interface

A data product is an interface towards consumption. Everything behind the interface is implementation — and should be free to change without making customers nervous.

That sounds obvious, but in practice this is the difference between:

- “we daren’t touch anything, because everything is intertwined”

- and “we can improve the engine room without phoning half the organisation”.

When you take the interface seriously, sharing becomes easier, change becomes less dramatic — and people stop creating copies “just in case”.

Outside vs inside

Outside (product surface) is what you stand behind over time: semantics, keys, time logic, recommended consumption path, change practice and expectations.

Inside (engine room) is everything you should be able to change frequently: staging, intermediate layers, pipelines, optimisation and refactoring.

Table, model, dataset and dashboard

It is easy to conflate the terms. Here is a practical clarification, primarily to keep discussions short:

- Table/view is a delivery format. Some tables are product surface. Many are internals.

- Model is how you produce the deliverable. The model is rarely a promise to the customer.

- Dataset is a useful umbrella term, but often imprecise as a product surface if it does not state what is official.

- Dashboard is presentation. It is typically a consumer, not a data product.

The point is not to be linguistically strict. The point is to be able to say: “This is the supported surface. The rest is engine room.”

How do we share data products within domains, across domains and externally?

A data product that cannot be shared is, in practice, an internal deliverable. And sharing is more than “publishing in the catalogue”.

In practice, sharing consists of three steps:

- Find

- Understand

- Get access

Many organisations improve only step 1 and are surprised that self-service does not happen. The catalogue looks nicer. Day-to-day life does not get easier.

The sharing journey: what needs to be in place?

Before you discuss tools and catalogues, it is worth checking whether you actually offer a complete sharing journey.

On the product side, you should always answer three questions:

- What is this (and what is it not)?

- How do I use it? (recommended consumption path + example)

- What can I expect? (access, refresh, quality signal, change)

If you cannot answer these briefly, sharing often ends up as private messages and verbal explanations. In other words: social capital as an integration layer.

Sharing within a domain

Within a domain, people have more context, a shared vocabulary and often a shorter path to sources. A simple practice therefore works well — as long as it is clear.

What typically works:

- shared entry point in the catalogue

- clear distinction between product surface and component

- short path to a point of contact

- simple change practice

Note that this is not about “more documentation”. It is about the right type of signal in the right place.

Sharing across domains: meaning before schema

Across domains, context disappears. What was “obvious” suddenly becomes a source of misunderstanding.

You then need to be precise about:

- terms (semantics)

- keys and time logic

- constraints

- change/notification

Sharing without shared terms rarely produces reuse. It produces copies.

If you only share schema, you often just share the ability to misunderstand faster.

External sharing

When you share externally, the game changes: expectations become higher, and the cost of errors becomes more apparent.

Here, contract, change and support must be explicit. In addition, compliance often becomes the driver for product surface and access.

A good sign of maturity is that you can answer:

- Who do we notify when something changes?

- What counts as “breaking” for external consumers?

- Who receives support enquiries — and what is the normal response time?

Data contract: use it when risk and dependency warrant it

Data contracts are not a goal in themselves. They are a tool for predictability when “hoping for the best” becomes too expensive.

Consider introducing contracts when:

- multiple teams are dependent

- the cost of errors is high

- change happens frequently

A simple decision rule can be: The more dependencies x the higher the risk x the more frequent the change, the greater the likelihood that you need a data contract. And in many cases, a “contract light” suffices for a long time (the fields people misunderstand, keys/time logic, and change practice).

Read more: Guide to data contracts