In practice: product page, catalogue and components

08.02.2026 | 4 min ReadTags: #data products, #data catalogue, #data component

How data products should actually look in a catalogue and in operations.

Why data catalogues often go unused

Many data catalogues do not fail on search, UI or “missing metadata”. They fail on signal.

When everything looks the same, users cannot get an answer to the most important question:

What is safe to build on — and what is merely an internal component?

If the catalogue does not answer this quickly, three things happen quite predictably:

- search becomes noise (you find a lot, but not what you dare use)

- trust drops (“what is actually supported?”)

- sharing ends up in private messages and verbal explanations

So if you want to “get more value from the catalogue”: stop starting with more fields. Start with a clear classification that actually means something in day-to-day work.

Product vs component

This is the core of the entire data product mindset in practice:

Data product = a managed interface towards consumption (the product surface you support). Component = building block / engine room (important, but without a product commitment).

That may sound academic, but the consequence is very concrete:

- When you say data product, you are also saying: “We have customers, ownership, a promise — and we handle change.”

- When you say component, you are saying: “This may change to improve the engine room. You can use it, but you build at your own risk.”

This is also where many stumble: they call everything a “data product” and end up with a catalogue that offers zero confidence. The result is “everything is a product” leading to “nothing is a product”.

Or: we have 1,000 data products, but really only 13 — except nobody can find them, because the other 987 data components claim to be a product.

The practical test

Ask these two questions, and you will land correctly more often than you think:

- If this changes tomorrow — who complains? (named consumers)

- If something breaks — who picks up the phone? (named owner team + point of contact)

If you cannot answer clearly, it is almost always a component (or an experiment) — even if it is important.

Two asset types in the data catalogue

The data catalogue should describe both components and data products. But it must make the difference visible.

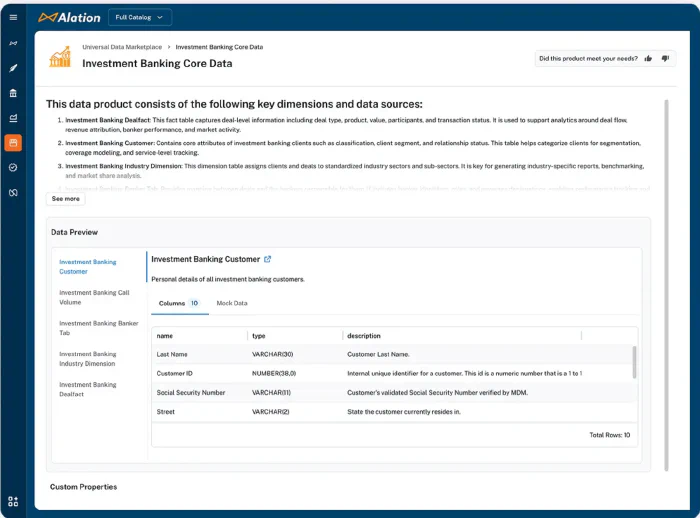

Data product: when you actually mean “supported”

A data product is the catalogue’s “front row”: things you want more people to use over time.

Minimum on a data product page:

- owner team + point of contact (not dependent on an individual)

- customers + value hypothesis (named customer groups)

- one recommended consumption path (the official product surface)

- access pattern without social capital (how to get access, not who you know)

- change/deprecation (changelog + notification + transition for breaking changes)

- contract light: keys/time logic + definitions people often misunderstand

- examples: “this is how you use it” (join, typical patterns, pitfalls)

Note that this is not “lots of documentation”. It is friction removal: Find, understand, get access.

Component: when it is engine room (but still needs to be tidy)

Components need less — but they must be clear that they are internals.

Minimum on a component page:

- owner (team) and point of contact

- purpose (one sentence that makes it understandable)

- lineage/dependencies (rough is often enough)

- classification for sensitivity/PII

- a clear statement saying: “This is a component (internal), not a supported product surface.”

The last point is undervalued: users cope well with something being internal — they cope poorly with being led to believe that an internal is a supported interface.

How to make the difference visible in the data catalogue

“Having two types” is not enough if it only says so in a wiki. The difference must be visible and filterable.

Distinctions that work

Start with the basics:

- a clear type:

Data product/Component - a visible badge in search and listings

- a filter that lets users choose “show only data products”

- a product surface marker that distinguishes “supported” from “internal”

- a simple lifecycle status on data products (draft/pilot/active/deprecating/retired)

If you get this in place, you will often see more catalogue usage without having “filled in everything”.

A practical rule for new deliverables

Start new deliverables as a component.

Promote to data product when:

- you have actual consumers you can name

- you can sustain a promise over time (ownership + capacity)

- you have chosen one supported product surface

This gives you natural portfolio management without introducing a governance regime.