Quality and reliability

08.02.2026 | 4 min ReadTags: #data products, #data quality, #SLO for data, #data observability

Three tiers, a handful of SLOs, and a response that makes people trust the product.

Quality is part of the product promise

When you say something is a data product, you are also saying that others can use it over time — without having to guess about freshness, changes or quality.

That is why this chapter is not about “perfect data”. It is about making the promise clear and operable:

- what does “good enough” mean for the named use?

- what is measured to detect deviations early?

- what happens when deviations occur?

“Good enough” means fit for purpose. Data quality can easily become a discussion without boundaries. In data products, the boundaries should be simple:

Quality = good enough for a named use, for a named customer group.

That makes it possible to be concrete. For many data products, three things matter most:

- Freshness: data arrives when it is needed

- Stability in semantics/keys/time logic: what you mean by “order”, “customer”, “revenue” does not change without control

- Quality signal: customers can see whether the product is “ok”, “degraded” or “stopped”

Tiers: not everything should have the same rigour

If everything has the same requirements, you typically end up with either too much governance — or too little credibility. Three tiers are usually enough to be precise without becoming heavy.

Exploration Data is used to learn and test hypotheses. The point here is to be clear that the promise is limited: frequent changes are acceptable, and you primarily need visibility (status + basic metrics).

Standard Data is used in reporting and ongoing decisions. Here you should be able to promise stable semantics for a defined use, and have a few tests/alarms you actually respond to.

Business-critical Errors carry high cost or high risk. Here the promise must be sharper: clear SLOs, a defined response to deviations and controlled change (which we build on in the next chapter).

SLOs: a few promises you can actually measure and follow up

SLOs work best when you are strict on quantity. Start with 2-4 per data product.

Most data products need no more than these categories:

- Freshness (refresh)

- Availability (readability)

- Quality signal (a few indicators that match the use)

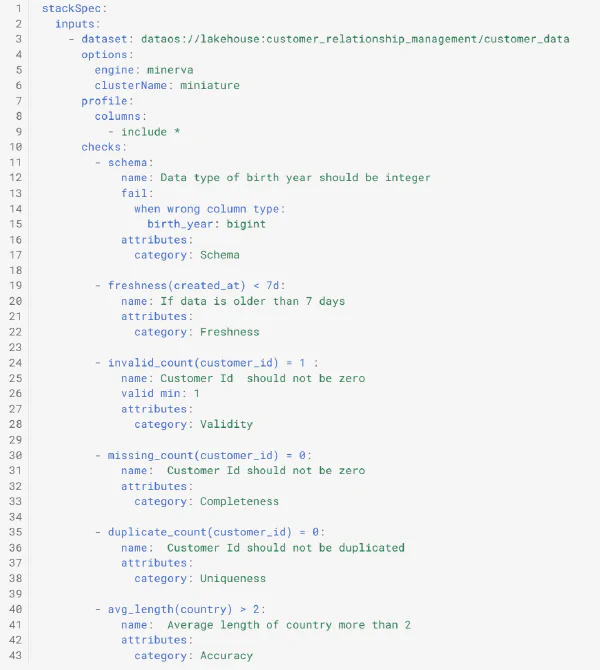

SLOs must be tied to measurable indicators. These are straightforward to get started with:

- minutes since last successful refresh (freshness)

- proportion of successful read attempts against the product surface (availability)

- proportion of null/invalid keys, duplicates on business key or invalid status values (quality signal)

The most important thing is not to choose the “right” metric on the first attempt — the most important thing is that you choose something you actually follow up on.

Response to deviations: stop, degrade or signal

Quality only becomes real when you have a clear response. In practice, three response types suffice:

- Stop: Used when the risk of misuse is high, or when errors have major consequences. The product is not published as “ok” if critical gates fail.

- Degrade: Used when the product can still be used, but with a clear limitation (for example “stale”, or a known portion of the content has deviations). Status must be visible on the product page.

- Signal: Used when risk is low, or during exploration. Deviations are made visible and notified, but without automatically blocking use. The point is that customers should not have to guess about the state.

Tests: a few that match the use beat many generic ones

Start with 3-7 validations that match the actual use of the product surface. Typically:

- mandatory fields

- unique keys (where uniqueness is expected)

- valid values (status/enum)

- referential integrity (where relevant)

- one or two business rules that frequently cause errors or misunderstandings

If you do not have a defined response to a failing test, that is a signal that the test is either poorly chosen — or that the threshold/responsibility is unclear.

Minimum for operability: a short runbook

For data products shared across teams, a short runbook is useful. It can be simple:

- point of contact + responsible team

- what does “stopped” and “degraded” mean for this product?

- most common failure sources (upstream/transform/access)

- where status and changelog are updated

It need not be more than that. The purpose is that both the owner team and customers get a predictable handling process.