How a community of practice can regain control of data engineering standards

23.11.2025 | 13 min ReadCategory: Data Platform | Tags: #Data Platform, #Architecture, #Data Engineering, #Data Mesh

Many organisations have decentralised product teams and a modern data platform, yet they still end up with a jungle of pipelines, tools and local solutions. This article shows how a small community of practice can establish shared data engineering standards — without taking ownership and velocity away from the teams.

Decentralisation often comes at the expense of standardisation

Many organisations have followed the same path: they have invested in a data platform, organised around domains and product teams, recruited talented data engineers — and yet they still end up with a jungle of pipelines, tools and “temporary” solutions that never stayed temporary.

Decentralisation was supposed to bring speed and ownership. Instead, you end up with multiple versions of the same key metric, and no one is entirely sure where the numbers come from.

By data engineering, we mean the work of designing, building and operating data systems that collect, store, transform and make data available at scale. When that work is done entirely locally, without any shared standards, the consequences are quite predictable.

When everyone builds their own “little factory”

In a data organisation without shared practices, the pattern is often the same. One team runs batch jobs in Airflow, another uses a cloud-native orchestration service, and a third has a homemade Python job with cron “until there’s time to tidy up”. The same concept — for example “consumption per hour” or “net volume” — is modelled in multiple variants, with slightly different logic and naming. Logging and monitoring ranges from well-structured dashboards to a log file on a server that nobody quite knows who owns.

The result is that:

- data quality becomes inconsistent, and trust in the numbers erodes

- costs increase, because the same problems are solved again and again

- time-to-market slows down, because each team starts by building the foundation from scratch

- risk increases, because critical knowledge resides in the heads of individuals

The teams are not doing anything “wrong” — they are solving local problems with the tools they have. The problem is the absence of someone with the mandate to see the bigger picture and say: “This is how we do this as an organisation.”

The community of practice: an enabler, not a control body

A data engineering community of practice can receive such a mandate. Not as a new control body, but as a small group that makes it easier to do the right thing, and a bit harder to invent your own standard for every pipeline.

The role is not to take over ownership of data products, write all pipelines or micromanage the domain teams.

The role is to:

- define a few, clear standards

- build and maintain reusable factory patterns

- help the teams adopt these in a pragmatic way

The goal is not to take back control in the sense of “centralised data warehouse 2.0”, but to make decentralisation sustainable.

Beware: A community of practice can also go too far. If every deviation must go through a committee, and every technology choice takes three rounds in an architecture forum, you have simply replaced local problems with central bureaucracy. The point is to create good standards, not to penalise everything that does not fit the pattern.

The community of practice in action

If you buy the concept so far, there are still several questions remaining. Who, how many and how often — and not least mandate and scope — must be clarified.

How many — and who should be in the community of practice?

If the community of practice becomes too large, it gets lost in coordination and clarifications. If it becomes too small — or filled with people who have no actual time — nothing happens.

A realistic starting point is: Four members, all data engineers.

A composition that can work in practice might look like this:

| Member | Type of team | Role in the community of practice |

|---|---|---|

| DE A | Domain with heavy analytics (finance, management, marketing etc.) | Represents strict reporting and data quality requirements |

| DE B | Operational / operations-adjacent domain | Represents the needs “close to operations” and the consequences when things fail |

| DE C | Shared platform/analytics team | Ensures that standards align with the data platform and operations |

| DE D | Team with high rate of change | Owns templates, example code and developer experience |

The community of practice should consist of people who write code, read logs and know the frustration when a pipeline fails at 03:15 — not just people who write principles documents.

Seniority and time commitment: what does it take for this not to become a hobby project?

It is easy to fool yourself here. “You can just do this on the side” is about the surest way to ensure that nothing happens. Experience is quite consistent:

Unless at least two people get around 20% of their time, little happens beyond meetings.

A model that works better:

- Two key people at 20% each: They drive forward code, frameworks and pilots. They are the engine of the community of practice.

- Two members at 10–15% each: They participate in design and review, bring the community of practice into their own domain, and contribute to health checks and training.

Translated into a practical work calendar:

- 20% is roughly one day per week of real time plus some asynchronous work.

- 10–15% is roughly half a day or two dedicated focus blocks.

If the organisation is unwilling to allocate that time, you should be honest: then this is a professional forum, not a community of practice with delivery responsibility. Such a forum delivers far less value.

Scope: What is in, and what is out?

A classic mistake is to push “everything involving data” into the community of practice: streaming, integration platforms, APIs, MLOps, master data, you name it. That is an effective way to break the capacity.

A clear scope might look like this:

| In scope | Out of scope |

|---|---|

| Batch pipelines for historical and periodic data | Streaming and real-time solutions |

| Data preparation for reporting and analytics | Integration platforms between operational systems |

| Data foundations for classical data science | MLOps and model operations |

The community of practice does not need to own everything — it needs to own what makes it possible to build good analytical data products without each team having to reinvent the wheel, the axle and the suspension every time.

Some areas the community of practice should take responsibility for

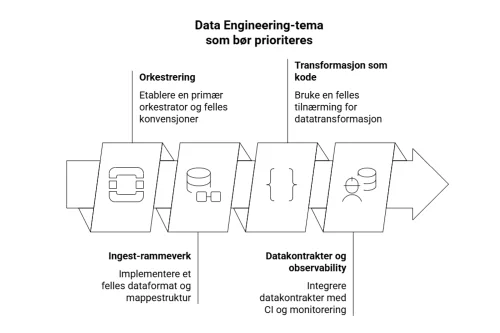

Rather than spreading thin, it is often more effective to work properly on a few core areas. One way to frame it is to envision a single concrete pipeline — for example the data foundation for a weekly management report — and ask: what needs to work for this to be predictable, reliable and understandable?

1. Orchestration The weekly run should be triggered, fail predictably, and be re-runnable without drama.

This requires:

2. Ingestion framework Data can come from financial systems, line-of-business systems and external sources.

Instead of each team defining format and structure themselves, you use:

3. Transformation as code The logic itself — filtering, aggregation and other business rules — should not be scattered across notebooks and ad hoc SQL.

A shared approach (for example dbt) provides:

4. Data contracts and observability Ultimately, it is about knowing when something is wrong before the leadership team sits in a meeting with numbers that do not add up.

This means:

Taken together, this makes a noticeable difference: Before, you had various scripts and tools, manual troubleshooting and the same errors in ever new variants. Instead, you have a known way to set up, run and monitor batch jobs — regardless of domain.

Other topics a community of practice can take responsibility for — once the foundation is in place

When these four areas start working, it is tempting to jump on everything else right away. That is not necessarily wise. But some topics are so close to the daily life of data engineers that they are natural “phase two” candidates for the community of practice.

5. Access control in the analytics platform The community of practice should not take over everything related to security, but there is a clear intersection where data engineers actually have their hands on the wheel: how access is implemented in the data platform.

This can involve:

The point is not to replace the security function, but to ensure that access models can actually be implemented consistently in the code.

6. Automated documentation through code “We’ll document it afterwards” is perhaps the most widespread lie in the data profession. A community of practice can make it a little less of a lie and a bit more of a reality, by building documentation into the tools and standards.

For example:

The goal is for documentation to be a natural part of the workflow — not a separate, outdated Confluence page that nobody reads.

7. Developer experience for data engineers If doing the right thing is cumbersome, people will do it wrong — or not at all. A community of practice often has the best overview of what actually makes day-to-day life frustrating or delightful for data engineers.

Typical measures:

This is not “nice to have”. A good developer experience is what determines whether the standards are used, or merely mentioned.

8. Cost and capacity — FinOps for data pipelines When everything runs in the cloud, there is a short path from a slightly too generous cluster configuration to a bill that hurts. The community of practice can play a practical role here, not as accountants, but as the people who know how pipelines actually behave.

This can mean:

The point is to make cost visible early, not when the invoice arrives.

9. Onboarding and competence development Standards and patterns have limited value if new data engineers start their own little ecosystem.

The community of practice is well positioned to define a simple "starter pack" for onboarding:

This avoids each new hire receiving their own personal version of “how we do things here”.

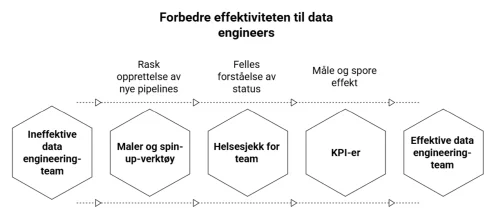

The community of practice must deliver more than guidelines

There are many intranets full of principles and “this is how we should do it” documents. What few people need is yet another one. What actually makes a difference is concrete artefacts that teams can start using next week.

Three things stand out as particularly effective:

1. Templates and “spin-up” tools A simple way to start new pipelines can be a cookiecutter project or equivalent that:

The goal is that a new team should be able to get started in one day — not one sprint.

2. Health check for teams A short health check gives both the community of practice and the teams a shared picture of where they actually stand.

It can cover things like:

It does not need to be more advanced than a simple score per area and some recommended actions. The point is to make the gaps visible.

3. A small set of KPIs A few indicators are enough to see whether the community of practice is actually having an effect:

The most important thing is not millimetre precision in the first instance, but that you can show a trend — and link it to concrete actions the community of practice has taken.

A realistic 90-day plan

To prevent the community of practice from dying in the PowerPoint phase, it can be useful to think in three simple steps:

0–30 days: mandate and people

30–60 days: build and test the first factory pattern

60–90 days: anchoring and decision

Without that last sentence, everything is just “recommended practice”. In that case, habits usually win.

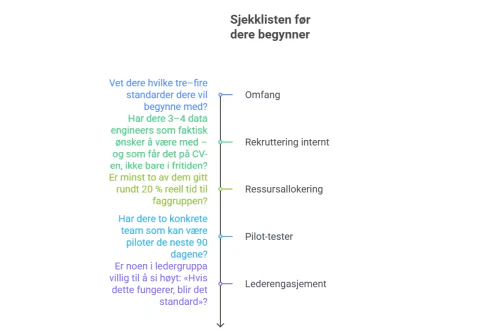

Are you ready for a community of practice? Five quick questions

Finally, a quick sanity check before you jump in:

If the answer is no to several of these, perhaps the time is not right yet. If the answer is mostly yes, you have a good starting point for a community of practice that does more than write documents: a small, effective mechanism for regaining control of data engineering standards — without stifling the decentralisation that was supposed to bring speed and ownership in the first place.