Data Platform | Historical Development

28.08.2022 | 7 min ReadTag: #data platform

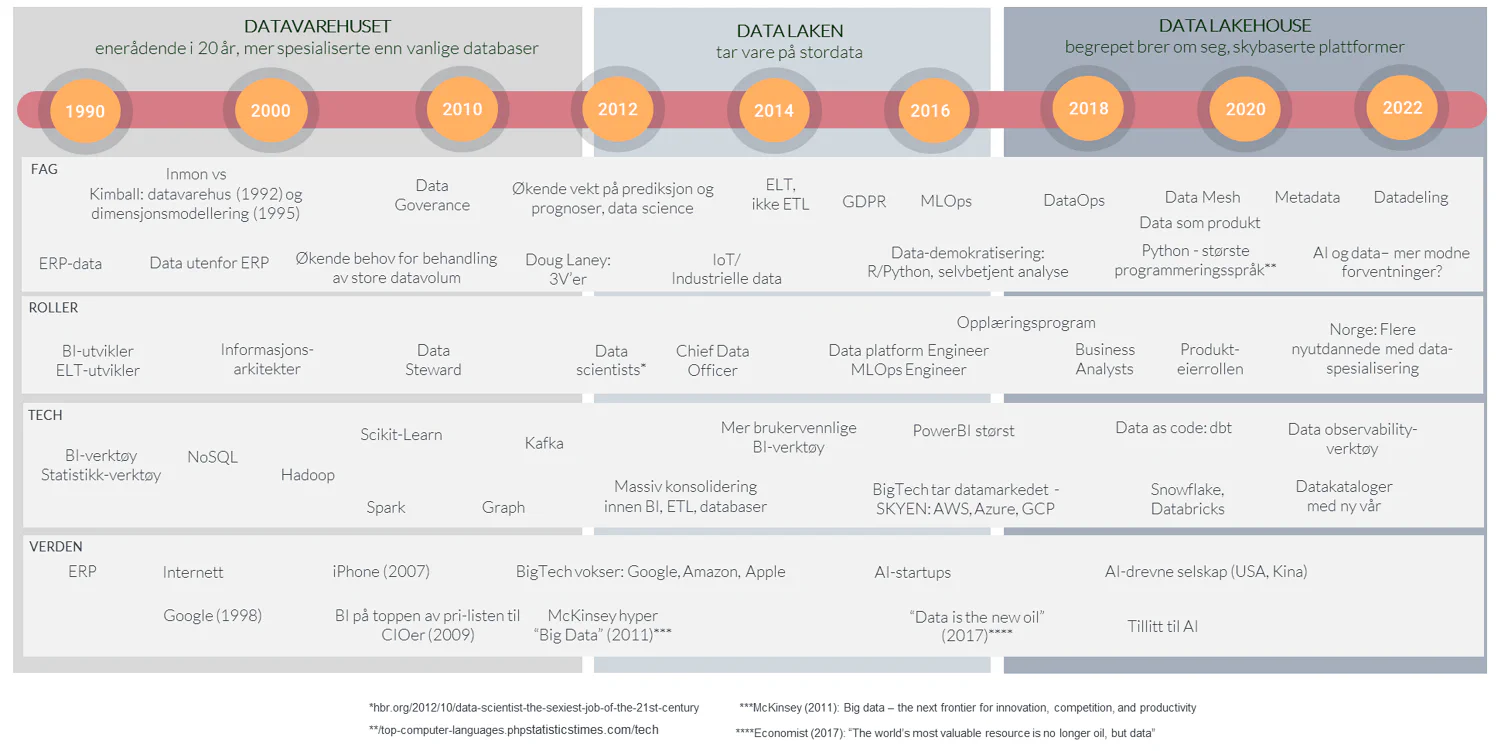

The definition of what a data platform is has evolved over time. The short version: we started with reporting on top of databases, moved on to 30 years of data warehousing, before data lake and now data lakehouse have taken over.

The data platform has a long history

1960 to approximately 1985: Databases emerge

Punch cards, mainframes and PCs appeared gradually from the 1960s through to the 1980s. For data and analytics, the truly great revolution came when relational databases made their entrance in the 1980s. These allowed users to write Structured Query Language (SQL) to retrieve data and create simple historical reports. In parallel, reporting and analytics software such as Cognos, SPSS and SAS emerged.

Approximately 1985 to 2015: The data warehouse supports historical reporting

Executives in large organisations in the 1980s generally did not know how sales and the bottom line were performing until after the accounting figures were finalised, often not until 15 days into the following month. The executives asked IT if they could fix this: “We have all this data in the finance system, in the production system and in the HR solution. Couldn’t you extract it and store it in a central place? Let’s call this place a data warehouse” (the executives did not actually say that, strictly speaking – it was Bill Inmon who coined the term).

“OK”, said IT, and purchased servers, software for integration, storage and visualisation. IT worked hard to extract the data from the source systems. Controllers and executives created dashboards with attractive graphs, where they could break down the figures by product, region, week, etc. As a result, executives could see how sales and the bottom line had performed, and organisations gained better control.

Over time, new roles emerged such as information architects, ETL developers, Business Intelligence developers and database administrators. Kimball and Inmon argued between themselves about how data should best be structured, and the discipline matured rapidly.

A billion-dollar industry was born. The tools for reporting, storage and data integration were still only moderately good, but we were on our way. The user threshold was somewhat high. The major players such as IBM, Oracle, SAP and Microsoft jumped in where previously we only had smaller companies.

Approximately 2012-2018: The data lake handles big data to support analytics

Around 2012, many began to struggle with the limitations of the data warehouse and looked for alternatives. Organisations had ever more data they wanted to analyse, and in addition they increasingly had web logs, video and audio that they wanted to store and analyse. But the data warehouse did not have the capacity, and moreover the servers down in the basement were quite expensive. They both cost a lot and were difficult to scale up or down in response to changing needs.

The data lake thus came into the world. Data lake technology had its origins in Yahoo, Google and the other new technology companies in the early 2000s. These companies generated massive amounts of data every second that they had to handle. There was significant technology development within the large data-driven companies such as Google and Amazon, and the major tech companies such as Oracle, SAP, IBM and Microsoft also bought their way into this growing market.

McKinsey helped create a hype around big data in 2011 with a report that brought data into the boardroom conversation: “Big data – the next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity”. The biggest hype came in 2012, with an article in Harvard Business Review titled “Data scientists – the sexiest job of the 21st century”.

We got new roles, such as Chief Data Officer and Data Scientist. There was a strong focus on using machine learning to solve all kinds of problems, but business analytics also came into the spotlight. It helped that the user threshold had been lowered in reporting tools such as Qlik, Tableau and Power BI. And not least, we gained greater flexibility and scalability through cloud-based infrastructure and services.

With all these possibilities, organisations no longer wanted to settle for looking at yesterday’s numbers, even in attractive graphs. Analysts, executives and subject matter experts all agreed: “We want to see what is going to happen, and not least predict which customers might leave us. Besides, wouldn’t it also have been nice to have avoided the quality variations we had in production?”. Machine learning and AI needed data and processing power to support these needs.

But the data warehouse could not deliver well on such user stories – there was too much data and, not least, too little flexibility. By contrast, the data lake with its architecture was well suited for storing large amounts of data cheaply. “We’ll dump all the data here”, thought IT. “And with Spark, we also have the ability to scale the processing of large data volumes”, they thought.

What many realised after pushing a lot of data into the data lake was that data without descriptions and practical applications provided little benefit. During this period, unnecessary resources were spent on data lakes containing data nobody needed, and on proofs-of-concept where machine learning was applied to problems that probably should have been solved with other and perhaps simpler methods. There was therefore somewhat less focus on establishing new data lakes after the biggest hype ended around 2017-2018.

As a result, IT eventually moved the most important data back to the data warehouse where they had routines and tools to maintain control. Many organisations therefore ended up having both one (or more) data warehouses and a data lake, with partly overlapping data and purposes.

At the same time, we saw companies like Spotify and Netflix basing their entire success on the smart use of data. The Economist wrote in 2017: “The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data”. Even though big data as a term faded away, most organisations continued to strengthen their use of data.

Approximately 2018: The data lakehouse concept gains traction

Since data processing had gradually become very important for many organisations and had reached the boardroom agenda, the data discipline received an update. Universities took the development seriously (somewhat belatedly), and started specialised study programmes in the data discipline.

We began working in agile ways and started talking about data products. Where the software development world had long talked about DevOps, we got this translated into the data world as DataOps.

Through the article “How to Move Beyond a Monolithic Data Lake to a Distributed Data Mesh” by Zhamak Dehghani, there was even more discussion in 2017 about how we wanted to organise ourselves to get the most value from data. It was healthy, and we still talk about this. The principles Dehghani proposed were not entirely new – she borrowed much from software development.

In terms of architecture, we got yet another term. Data lakehouse is an architectural pattern that was introduced by Databricks in 2018-2019. In their definition, they seek to process data where it resides, and remove the distinction between where data warehouse data and data lake data are stored. In other words, we have merged the data warehouse and the data lake.

A major advantage of the data lakehouse concept is that we avoid two competing architectures, used for reporting purposes (the data warehouse) and analytics purposes (the data lake) respectively.